I posted this comment under the article What can we learn from the sinking of the Bayesian? in the maritime journal Splash247.com.

Matt Bracken says

I was a sailboat rigger in Fort Lauderdale Florida in the 1980s. (“Rigger’s Loft”) At times we worked on masts well over 100 feet tall, so big I could not reach my arms around them. Large road cranes were required to lift these masts from horizontal to vertical for stepping. With the mast stepped, a large road crane was required to lift the roller furling jib systems. I can remember being in a bosun’s chair at the masthead putting in a “pin” almost the size of a can of tennis balls to secure the eye at the top of the jib furling system. This “pin” had a second pin at 90* to secure it, and that 2nd pin had its own giant cotter pin!

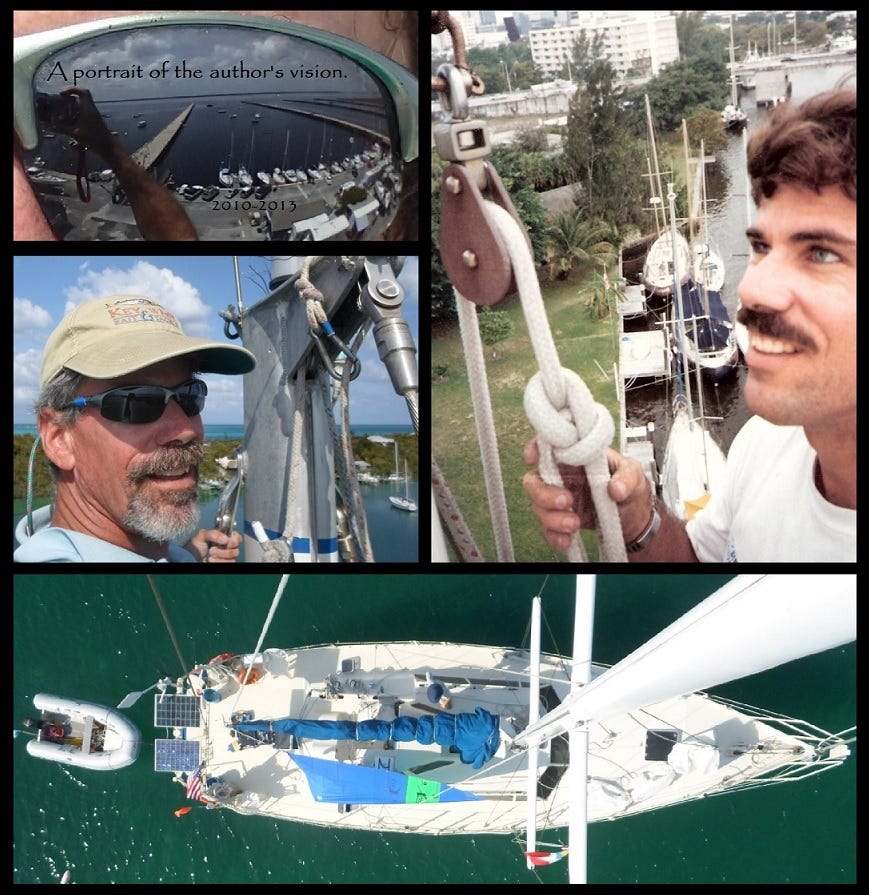

On the pier, It took two men to carry a single rigging turnbuckle on their shoulders like an elephant tusk. It could take a dozen or more men to carry a folded mainsail into position for installing it. I could go on and on. I also built my own 48′ steel sailing cutter in the 1990s and I’ve done major trans-ocean voyages both with crew and solo. I’m mentioning all this to establish some bona fides.

When we worked on mega sailing yachts, (over 100′ length on deck) I was always dubious about the “ballasted centerboard” concept. I was assured the stability curves had been worked out. It’s always a battle between yacht size, mast height and draft with the ballasted board down and the board up. The fixed ballast is in the hull, so not very deep.

Designers and builders want to design and to build, and many millions of dollars are involved. But when analyzing the stability curves, it was always obvious, at least to me, that if knocked down, these yachts would be in extreme danger. Once the mast is in the water, it’s going to begin to fill with water through a dozen or more mast openings for halyards etc. Once it’s filling with water and it’s weight doubles and triples, there is almost zero chance of a mega sailing yacht righting itself. IMHO.

At anchor hatches and vents will be open, this is just a fact of shipboard life. Crew and guests are moving in and out. Generators and HVAC systems need fresh air. Once knocked down with the mast horizontal, down flooding and sinking will be extremely rapid. The 1986 loss of the Pride of Baltimore One in the Atlantic is a case in point. She was knocked down by a “white squall” under sail and flooded through open deck hatches and sank before all the crew could escape.

Sailing ships were always at risk of a knockdown at sea, but their organic cotton sails and hemp standing rigging and sail control lines would often fail before a ship’s masts were in the water. Even dismasting was preferable to a knockdown. With sails and standing and running rigging made of modern synthetic materials, a mast and sails will not fail. Bayesian’s mast system did not fail. It held perfectly, taking her all the way over to 90*. Once there, she was virtually doomed.

One more point, and it’s not frivolous. With a centerboard down under sail, with a vessel heeled, the board is firmly positioned and pretty much as quiet as a fixed keel. But running downwind or at anchor, the rolling of the vessel will make the lowered centerboard “work” within its trunk. That “clunking” sound some have referred to will drive anybody out of their minds. For the board to be free enough to raise and lower, it’s going to have some play. With the board down, but minus the press of sails causing the boat to heel, the board is going to make enough noise to keep everybody awake at night. More thought has to go into keeping them quiet when they are down. If the board had been down at anchor, Bayesian might have been saved.

The crew had conflicting demands: persons and air needed to get in and out of the hull, but once over on her side, the water was going to come in through many hatches and vents. Ironically, it would have been safer for all concerned if Bayesian’s mast HAD failed. A dismasting would have been preferable to a knockdown. I don’t blame the designer, the builder, the owner or the crew. Nobody foresaw a knockdown at anchor. But a new look at stability requirements needs to be undertaken. Even a dismasting would have been better than what happened.

Below is another excellent Bayesian article I found on Substack:

My last three novels are largely set on and around a fictional sixty-foot steel trading schooner. Ironically, in my last novel, Doomsday Reef, there is a knockdown and dismasting. All of my printed novels are available at Amazon, or directly from me. The Kindle and Audible versions are only available from Amazon.

Matt is right about the thumping sound of a swing keel while at anchor or on a run. Even on our Catalina 22 it is so annoying.

Clear description of a complicated matter. Thanks