Drone Warfare Comes to Mississippi

An excerpt from my novel Foreign Enemies And Traitors, which I wrote circa 2009.

The deer stand was one of Zack Tutweiler’s best thinking places. The rain had masked the sound of his climbing up the tree’s nailed-on steps and into the plywood box an hour before dawn. The blind’s roof sheltered him from the rain. For as long as seventeen-year-old Zack had been allowed to go hunting by himself, the blind had been a place he could go without being hassled for choosing solitude. He brought home enough meat that nobody bitched about his disappearing with his compound bow into the forest. Now there was nobody left to bitch at him for anything. He was the last one still living at the end of Bear Trail Road, the last inhabitant of their refuge from the world.

The Tutweilers had hidden very well, but not well enough. The troubles of the world had sought them out in spite of their preparation, their camouflage and their faith. All the praying in the world had not prevented the flu from choking the life out of his twin sisters Becky and Annie last winter, the winter of the hurricane floods and the great earthquakes. Becky had died first and Annie a day later, both drowning in their own lung fluids. Zack and his family had prayed continuously, to no effect.

And praying hadn’t stopped the raging infection from killing his eleven-year-old brother Sammy last September. He’d gashed his knee with a hatchet while helping to trim the branches off their winter firewood. The most powerful antibiotics in their family medicine chest couldn’t stop that infection, and poor Sammy had died in horrible pain. Zack had helped teach Sam how to use the ax, but he had not taught him well enough. And now his little brother was buried in the cold ground forever.

After Sammy died, the praying had stopped, even Mom’s praying. This was some months after Mom had run out of her blue pills, the ones for her depression. These days when pills ran out, they ran out for good.

All along Mom had been waiting for the Rapture and praying for the Rapture, and in the end it was all for nothing. “We sure got the tribulation,” she’d often say, “But when, oh when, are we getting the blessed Rapture?” It wasn’t long after Sam died that she took the baby up to the bridge. “Rapturecide” is how Zack often thought of it.

Dad said she must have had an accident, probably baby Sarah had slipped and Mom had tried to save her, the river all swollen and running fast…but in his heart Zack had never believed this. He didn’t know if Dad believed it either, but he’d never challenged his father on the issue. It would have brought nothing but pain, and pain they already had to overflowing. They found Mom stuck in the rushes along the bank, but they never did find little Sarah. Dad said it had to have been an accident, but even he didn’t sound convinced.

But Zack knew what had happened, in his mind he knew. It was Rapturecide. He’d heard the term whispered at the swap market, at the cross-roads town of Walnut, Mississippi, a half-hour bike ride away. Sometimes whole families had gone that way, in their exhausted desperation challenging God to put up or shut up, once and for all. If they were not among the chosen, selected to fly up to heaven and avoid the tribulations, then who was? They were true believers, and God had forsaken them. Zack didn’t believe in the Rapture business, but he knew that many others did. When their deepest belief was finally shattered and crushed, the life quickly went out of them.

Zack had a clear mental picture of their final moments, gleaned from a thousand imaginings. Mom standing on the low steel trestle of the railroad bridge over the Little Hatchie, clutching baby Sarah to her heart. The dark creek running high and swift on the floods just beneath her feet. Staring heavenward through the clouds and making the final leap for everlasting glory. Giving God one last chance to carry them up on angels’ wings, to relieve them of their unending earthly travails. This was on the tenth of October, after it had rained for forty straight days. Mom had hardly spoken a word in weeks, not since little Sammy died, and she hadn’t smiled in even longer. And then she carried baby Sarah down to the river, in the never-ending rain. One of the few remaining bridges around, and it was her launch pad to heaven, according to Zack’s reckoning.

So if God was watching, He’d flat missed His chance to perform a miracle. Or maybe not, maybe God had snatched up their eternal souls anyway, because of her great demonstration of faith in Him. Maybe God had simply allowed their mortal bodies to fall into the swift current. Zack often wondered about this point: was faith alone enough to cancel out the sin of suicide? Mom just couldn’t bear living anymore. It was too hard, much too hard, especially after losing Becky and Annie and Sammy—and after running out of her blue pills.

Their lives had been hard before the hurricane floods and the earth-quakes, but Dad had prepared them well, moving the family from Tupelo up to the Holly Springs National Forest near the Tennessee line. Moved them from the city to the hidden dead-end Bear Trail Road, to the cinder block house he’d built with his own strong hands. Dad was a survivalist even before the crash, before the Greater Depression had set in. He’d had foresight; he’d been one of the few mad Noahs who had seen the great flood tide of misery coming, back when there was hardly an unhappy cloud to be seen in the then perpetually blue Mississippi sky.

Against every friend’s recommendation and well-meant word of family advice, they’d left their comfortable home in Tupelo and moved to their own five acres on the uppermost edge of Mississippi, backed right against the National Forest. They had water from their own well, they had firewood and chickens and enough stored rice and beans to last for years. Even after the dollar crashed to nothing, they hadn’t starved. They could survive, even without electricity from the power grid this last year, since the quakes. They had hidden from the looters, robbers, and gang-rapers after the quakes, they had survived all of the visible dangers, but Bear Trail Road was not hidden from the epidemics. Their refuge was not hidden from infections that no antibiotics could defeat. And Bear Trail Road was certainly not hidden from the affliction of despair, not when the flooding Little Hatchie River whispered its siren song to Mom’s beaten-down soul.

Then it was just the two of them, father and son, and even then they could survive. They had buried all of the rest of the family, had shed rivers of tears, but quitting was not in Dad’s vocabulary. Zack had grown up hearing that and he knew it was true. Dad would never quit—Dad was the rock. His father prayed, but he didn’t believe in the Rapture, and he would not hasten his way to joining his family on the Other Side. Father and son would continue to struggle, they would push on, and they would survive.

They would emerge intact on the other side of the long emergency, if it were in any way possible. Zack was nearly eighteen, almost “of age,” Dad had said. Zack Tutweiler would find a girl to marry, and the family would not die. Tutweilers had survived wild Indians, the Civil War, the Spanish flu and the Great Depression, and they had not yet been pushed out of Mississippi. Tutweilers had fought in every American war, but enough of their men had returned to Mississippi to carry on the name down through the generations. They were people who knew when to lay low and when to push back and when to fight with animal ferocity. Quitting was not in their vocabulary, which is why Dad clung to the threadbare belief that Mom had gone into the river to save baby Sarah.

And so it had been only the two of them these last months, until a week ago. Dad had gone out after midnight. He had people to meet over the state line in Tennessee, trading partners who couldn’t come to the swap markets in Walnut or Corinth. Sometimes Zack accompanied him on these walks, but more often not. When Dad went out alone, Zack stayed up waiting, although he pretended to be asleep when Dad slipped out of the house. But that last time he’d heard a single echoing bang, and his father had not returned.

He didn’t find his father—what was left of him—until the middle of the next day. He was in the National Forest a mile northwest of their home, almost on the border. His father had been blown to pieces, his powerful body shattered. Even his shotgun had been blasted into a bent piece of junk. Zack hid in the woods near the human fragments of his father, shaking, crying, and wondering what to do next. He also found pieces of rocket casing and what was probably part of a rocket tail fin knifed into a tree near the body. His father had been killed by one of those little missiles that dropped down from the unseen drones. He knew of them from his dad, who had heard of them from the men he met in Tennessee. He’d never imagined his father would be killed by one, not in Mississippi.

So now Zack was the last of the Mississippi Tutweilers, who the Indians and the Yankees and the Spanish flu couldn’t kill off. The end of the line. He’d sometimes considered following Mom and Sarah into the Little Hatchie, but even in death his father’s voice was stronger: Tutweilers don’t quit. They might get knocked down, but they always get back up. But what was the point of remaining in Mississippi now? The men who had killed his father were in Tennessee, he thought. This was why Zack was up in the deer stand on Christmas morning, thinking, watching the first hint of false dawn appear above the treetops, where the dead power lines cut a swath through the forest leading up into Tennessee.

Now was the time the deer moved. Night fog hung low over the ground. Sometimes he’d see antlers before he’d even see a deer, but more often the bucks pushed the does out ahead: no dummies they. Well, a doe would serve him just fine, he could trade the fresh meat to the Mississippi Guard soldiers stationed at Walnut. His eyes strained to see down the game trails that ran in the brushy terrain beneath the hanging power lines, beneath his deer stand of green-painted plywood. It didn’t need to be camouflaged. Deer weren’t made to think about odd shapes, like the square green box nailed to the branches twenty feet above their trail.

Movement in the shroud of mist attracted his eye. Most of his face was hidden behind the square shooting hole in the south side of the blind. He saw the tan-gray color of a deer, moving cautiously in the underbrush, pausing, and moving again. Zack silently shifted to one knee and brought his compound bow up, an arrow ready, his right hand gripping the string’s trigger release.

The shifting tawny shape slowly emerged through the ground fog, but it soon became apparent that it was not a deer at all—it was a man. A man coming up one of the game trails, northbound. A man with a pack on his back, a man wearing the camouflage uniform of the Army, a matching wide-brimmed hat concealing his face. Zack shrank away from the shooting port and put his eye to one of the peepholes. Deer would not pay attention to a plywood box suspended from a tree, but a soldier would. The solitary soldier could be a point man. He could be a few yards ahead of a squad or a platoon, probing for booby traps or ambushers.

But as Zack peered at him, he noticed some things that didn’t fit. The man had no rifle or machine gun; in one hand he held a pistol. No point man would come this way armed with only a pistol. But the lone man was wearing the new camouflage pattern uniform of the Mississippi Guard and the United States Army, and it was forbidden on pain of death for civilians to wear it. So the man was a member of the Guard, or he was an Army soldier—or had been.

The drone that had dropped a rocket on his father had been fired by such men. His father was out after curfew, of that there was no doubt. And he was carrying an illegal pump-action shotgun. The government had, he guessed, every legal justification to blow him up with a rocket for violating those two laws. That’s the way the world worked under martial law. Zack understood this, but it didn’t make him feel any better about it.

This soldier was alone, Zack finally decided. He was one of the soldiers who helped to fly the drones, who dropped the missiles on the curfew violators. Men like him had dropped the missile on his father. Was he out checking the results of another missile drop, like the one that had killed his father? No. Alone and armed only with a pistol, he was more likely either a spy or a deserter. He could be a military spy from Tennessee, on his way back to make a report. Maybe he was even one of the foreign “peacekeepers” in an American uniform.

The man paused for a solid minute, looking in all directions, and stared up at the boxy deer blind. Zack knew it must be clearly outlined against the pale dawn sky. But the man had no heat-sensing infrared scope, so Zack trusted that he was invisible in his box—as long as he remained motionless and made no sound.

Finally, the man looked around in a wide circle and continued walking a few steps at a time, passing less than thirty feet away, directly in front of the blind. Zack slowly shifted to another peephole in the long side of the blind, and he saw the man going away now, walking north up the game trail below the power lines, with brush and saplings and bushes up to his shoulders. It was winter and the shrubs were mostly without leaves, so he could easily see the soldier through them.

Without thinking, operating on automatic, Zack twisted around in the box and rose to a one-knee crouch, his compact bow rasping against the interior plywood, almost but not quite silent. The arrow was nocked into the string, his trigger release was ready in his right hand. He rose to a crouch and took aim through the square cutout on the north side of the box. He took in a breath and held it, drew back the seventy-pound pull string, and put the glowing orange plastic bead sight on the man’s back as he reached full draw. The compound bow’s wheels rolled to a stop, held for a moment—and then he let fly.

Phil Carson heard something scrape behind him and he turned to his right, just beginning to twist and dive when he was struck. He fell onto his face in the wet underbrush, rolled onto his right side, his pack preventing him from rolling onto his back. He saw the arrow buried in the ground just ahead of him, feathers aiming back at the tree stand behind him. Already his leg was going numb, and his hip and backside burned. What an idiot he’d been, taking the easy path, stumbling up the power line right-of-way, not even sure if he was in Mississippi or Tennessee. The moment he was hit, he’d known the arrow had come from the wooden blind he’d just passed. He had studied the boxy deer stand but he’d ruled out that it might be occupied. He’d disregarded the potential danger, eager to make time and get as far as possible into Tennessee before full light.

Now he’d been skewered by an arrow, and he knew the unseen hunter would be drilling him again any second, would nail him to the ground. He’d been sneaking up a game trail, surrounded by bushes that were head high or better, so perhaps he was now invisible from the blind, hidden down among the dripping ferns on the forest floor. The arrow seemed to have sliced through his left thigh or buttocks, gone all the way through and out again. There was no way to know how badly he’d been injured, and no time to examine the wound.

Carson knew the hunter would be coming down out of the stand, following his wounded prey, looking for another shot, eager to put a fatal arrow through his vitals. If he was going to survive even the next few minutes, he had to move, regardless of the pain, no matter how much he was bleeding. The backpack was too heavy; he released the chest and belly straps and awkwardly slid his arms out. He kept the pistol in his right hand, and using his elbows and his uninjured right leg, he began to push himself away from the game trail into an evergreen holly thicket. He wormed his way into the almost clear space at the very bottom, and out again on the other side into an area of roots and wet leaves and bushes and small pines like Christmas trees.

Seconds counted. He ignored the pain and low-crawled ahead a dozen more yards, fully aware that he was leaving a trail of blood and broken vegetation a blind man could follow. His creeping path brought him alongside a massive deadfall pine trunk, bare of bark to its yellow core. It had fallen long ago, and once it became rotten it had broken into segments following the contour of the ground. When he reached the end, where its roots had once upended the earth, he turned sharply around it and pushed his way rapidly back in the direction he had come, racing against time, against the bow hunter he knew was coming. The earth was lower on this side of the trunk, lower and eroded, and he pushed his body into the hollow space alongside the bottom of the log. When he came to a break where the rotted log had broken into two pieces he stopped, his face pressed against the pungent mud and wet wood punk and loose forest litter, and he waited, with just one eye looking up through the gap.

He didn’t have long to wait. The hunter was dressed in camouflage raingear, the pattern he recognized as something like Mossy Oak, so similar to the background of the wet winter forest that he almost appeared to melt into it each time he stopped. He carried a small camouflage-painted bow, an arrow at the ready but not drawn back. He was walking in a crouch, pausing to snake his way through the underbrush and, it appeared, to stoop down and touch Carson’s blood trail. The hunter’s parka hood was pulled up, covering most of his face, a puff of vapor visible with each breath.

The hunter approached in short, quiet steps, until he was on the other side of the rotten trunk. In spite of the pain and steady blood loss, Carson felt a measure of satisfaction. The hunter was used to following the blood trails of herbivore game like deer, animals that went deeper and deeper into cover until they found a place to rest, and then to bleed out and die. Deer didn’t double back. Deer didn’t fishhook their own path, to lay an ambush for a pursuing hunter.

The bow hunter moved silently, pausing to listen and look, then took a few more steps, the wet forest litter masking any sound. He reached the break in the log on the other side of Carson’s head; Carson’s body was still hidden in the hollow beneath the log against the wet earth. The bow was carried with the arrow pointing at an angle to the hunter’s left, away from his hiding place. Carson held his Beretta alongside his cheek, pressed against the dirt and leaves. His head was turned so that he could peek from under the brim of his boonie hat, up through the break in the deadfall log. The hunter’s face slowly turned toward the foot-wide break in the rotted trunk, his arrow still aimed away, and he stared downward. Carson saw in the hunter’s altered expression the very instant that he recognized the uniform in the forest litter on the other side of the log. In that moment of mutual recognition, Carson thrust his arm and pistol upward through the break in the spongy log and began to squeeze the trigger, the Beretta’s first shot requiring a long double-action trigger pull.

The hunter’s bow swerved around, but the arrow snagged on a sap-ling branch and stuck. In the next moment Carson saw a boy’s wide-eyed face looking back at him, and he stopped the tightening of his trigger finger in mid-squeeze. The young hunter jerked at his bow, trying to free it, still staring into Carson’s face with huge brown eyes, his mouth wide open.

“Don’t you do it, boy! Don’t move, if you want to live.”

* * * * *

(I wrote Foreign Enemies And Traitors around 2008. It doesn’t seem so far-fetched anymore.)

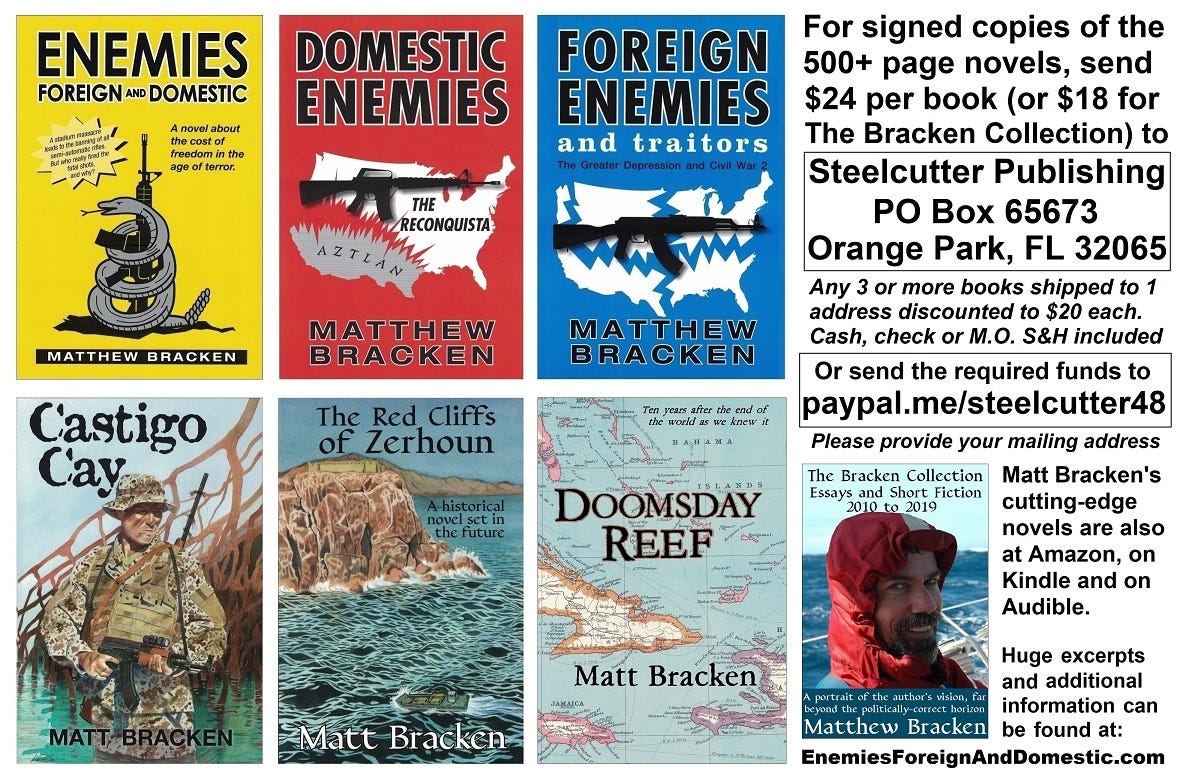

All of my novels can be obtained directly from me, and I’ll sign them. Snail mail works, but paypal.me/steelcutter48 is the fastest method.

(Or you can get them from Amazon in print, Kindle and Audible versions.)

Much more info can be found at my website EnemiesForeignAndDomestic.com

Can't believe I wasn't already subbed here...I've been remiss.

I've read the first book in the Series. It was a great story but the last couple of chapters were bittersweet.