One of the most gratifying aspects of being an author is occasionally getting surprises in the mail. Today's package came via a paper notification in my little PO Box, because the 2-foot-wide painting, well boxed, was still too big to fit into any of the other boxes at the Post Office.

The painting shows the opening scene of The Red Cliffs of Zerhoun. Captain Dan Kilmer, on the right, is sharing a corner table in a cozy Irish pub with Dr. Victor Aleman. This pub is in the tiny port of Crowhaven, in County Kerry, in SW Ireland. The artist even worked a crow up into the top corner. I'm very touched when readers are inspired to send me works like this; they are among my most treasured possessions. Sorry for the poor reproduction, I just took a photo of it on a table. Sincere thanks to Mr. Davis in Georgia. The photo does not do justice to your work.

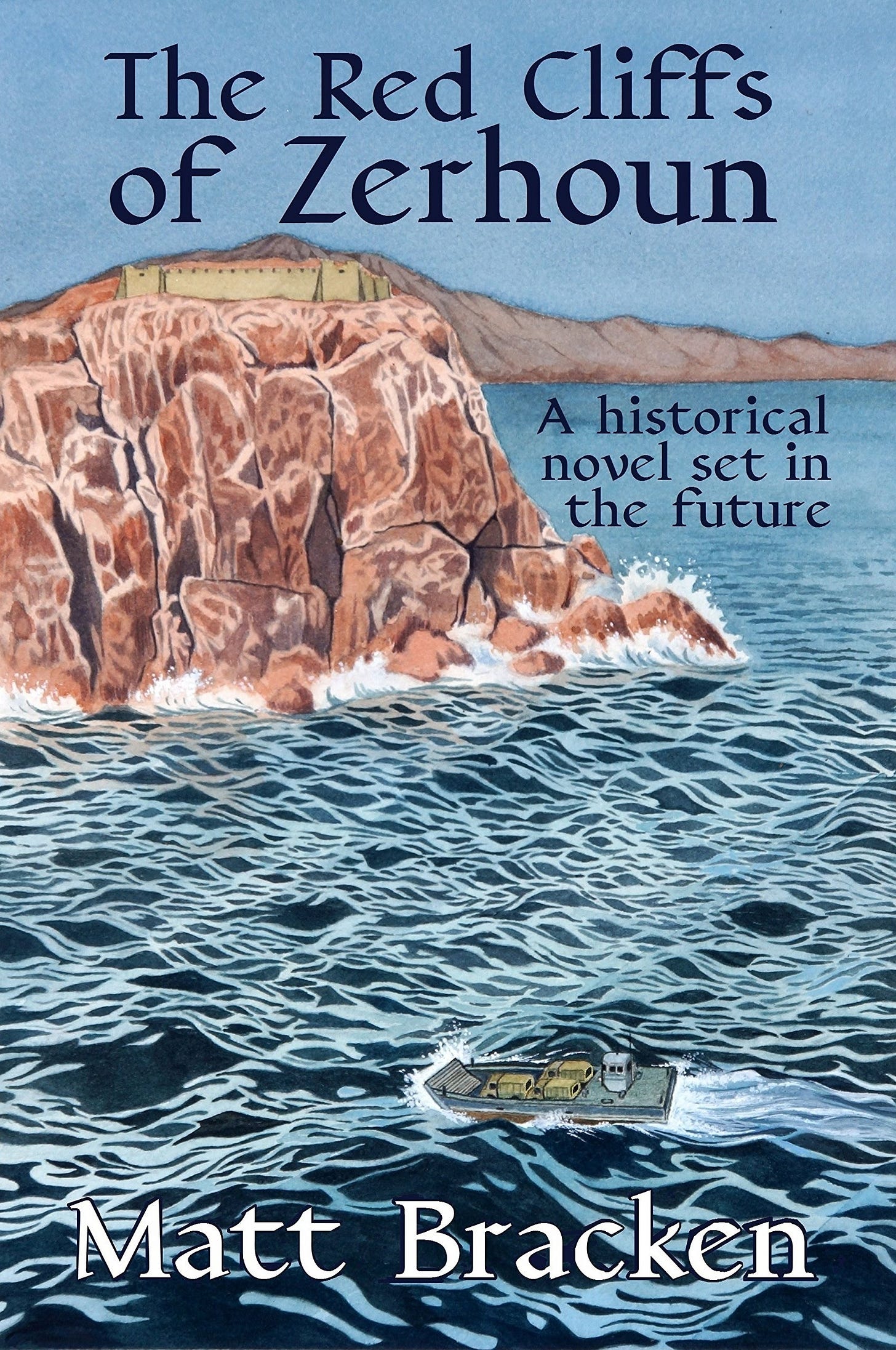

The art for The Red Cliffs of Zerhoun is by Mark Kohler. He's an accomplished painter who wanted to create covers for my novels after the Enemies Trilogy. He also did the cover art for Castigo Cay. Here's a link to his website, Mark Kohler Studio.

And here is the first chapter of The Red Cliffs of Zerhoun:

We were sitting in the corner of a gloomy Irish pub, its only customers. Victor was across the table from me. There were half-finished pints between us, along with a few notepads, books, binoculars, and other personal clutter from spending most of the day there. Peat burning in an iron stove helped to drive off the autumn chill, but even inside the pub we wore sweaters. We could have moved closer to the heat, but then we would have lost our corner window position.

The aroma of the peat, or turf as they called it, made the place seem cozy and welcoming when you stepped inside. After two weeks of adapting to the local ways we might have been taken for locals, if we kept our mouths shut. Our front corner table had windows on two sides, and we could watch both the road leading out of Crowhaven and my sailboat at anchor a hundred yards away.

This rocky outcrop of southwest Ireland was as close to continental Europe’s ongoing civil wars as I cared to drop anchor while engaging in a commercial venture. A month earlier we had left an abandoned NATO air base on the west coast of Greenland with ninety-six drums of diesel fuel loaded two-deep in our cargo hold. A tight fit, and my sixty-foot schooner had her waterline submerged by a foot from stem to stern on the voyage. With a virtually infinite amount of fuel aboard, we ran the engine nonstop for a week, motoring all the way to Ireland.

The rain had let up and I had a decent view of sections of the road as it wound its way up into the hills from the tiny seaport. We had staked out the strategic table by paying in silver coin for our pub fare. Not that there was much demand for this or any table in the establishment. In fact, the two of us constituted much of the pub’s daytime business. Some cars, minivans, and small trucks were parked outside, but few of them had moved in the two weeks since we had opened shop. The brewery van, greengrocer, and various fishmongers made periodic visits, but hours went by without the arrival of another patron. Vehicles moving on the visible sections of road were rare enough to make our task of surveillance easy. Slow-moving pedestrians, bicyclists, and horse-drawn carts were more frequently seen than cars or trucks.

Aside from potential customers, we were keeping an eye out for the Garda, the Irish national police force, or anybody else who might attempt to remove our cargo without paying for it. In an hour, when it grew too dark to observe the distant hillside, we would return to my schooner and have our evening meal, spend the night at anchor, and then return to the pub the next morning.

Hung, my elderly Vietnamese cook and boat guard, would already be at work in the galley. He’d been with me since I’d picked him up in Trinidad a decade back. He spelled it Hung when he had to spell it, which was rarely, but it was pronounced Hoong. His family name was Tran, so his full name was Tran Hung. Besides being a great sea cook, Hung is the reason I can leave my boat at anchor with no worries.

The late October daylight was fading fast. Victor had just returned from a long walk on the rural lanes of the surrounding countryside. When ashore, and when the weather was fair, Victor was big on hiking, or trekking, as he sometimes called it. He was always looking for a steep hill with a sweeping view from the summit. Sometimes with me as his companion, and sometimes without.

Victor liked to appreciate geological formations at close range, explaining how many millions of years ago this or that outcropping had been thrust up from the sea floor to become part of a mountain, which had then been worn down by glaciers and erosion to become what we were presently standing upon. Southwest Ireland was also replete with castle ruins on hilltops, and we had already visited several of them. In another era, I would have taken loads of photographs. I had thought that our recent Irish treks would have put Victor in a good mood.

He put down the tattered paperback novel he’d been struggling to read in the lowering light and said, “Another day, the same stale rumors, but still no customers. How long are we going to remain here? The longer we wait, the greater the chance that we’ll be arrested, or robbed. If there were any more local customers, they’d have found us by now.”

“It’s more than a rumor.”

“More than a rumor? Only according to your lady friend.”

“My lady friend has a name.”

“Sinead Devlin.” He rolled his eyes and sighed. “And I’ll admit she’s quite attractive, so I understand perfectly well why your thick American brain is not functioning correctly. Visual stimulation and chemical pheromones. Mammalian biology, nothing more. So be it. But how long will we wait here? It’s getting colder every day. And darker.”

“Maybe another week, maybe two.”

“And then we’re going to South America, correct? That’s still the plan?”

“That’s still the plan.”

“No more stops in Europe? Not even Spain or Portugal?”

Victor had been kicking around the Atlantic with me almost as long as Hung had, and now he wanted to revisit his homeland of Argentina. I didn’t understand why. He had no living family there, at least none who would recognize his blood connection to them. Victor was the bastard son of an escaped Nazi officer and his late-in-life mistress, a Buenos Aires “dancer,” to put it politely. The old Nazi had done very well in the import-export business after landing in Argentina in 1946, but his German-Argentinean family did not consider the much-later-arriving Victor a member in good standing of the new clan. He had received a first-rate education in Argentina and Germany, but the tenuous family connection was severed with his father’s death.

I said, “We’re going to South America. That’s where we’ll repaint and refit. But we’re not going there in a straight line. We’re low on propane, and I don’t want to cross the ocean eating cold food. And if Sinead comes aboard, we’re going to spend the winter in the Caribbean. That’s just how it is. She’s never seen a coral reef or a palm tree in her life. But first we’ll stop in Madeira. Maybe we can get propane there.”

The Portuguese island of Madeira lay halfway between the Azores and the Canaries. I hoped that visiting the nearly idyllic semi-tropical island would make Sinead fall in love with the cruising life. Enough to inoculate her against the tedium, bad weather, and seasickness she would also undoubtedly experience.

It would be a challenge to adapt her pale Irish skin to the burning tropical sun, so best to take it in easy steps. It was a challenge I looked forward to, along with teaching her how to sail and skin-dive and introducing her to all the other joys of a tropical pleasure cruise. But my new Irish girlfriend was not yet committed to coming along on the voyage. And we still had a third of our original cargo of diesel fuel to sell.

Victor closed his book and studied me over his gold-rimmed glasses. “You are letting a woman dictate your schedule again. Don’t you remember what happened the last time?”

“Yes, and the time before that.”

He sighed. “And a ginger with green eyes. You’re absolutely mad.”

“She’s not a ginger,” I said. “She has brown hair, and her eyes are hazel.” To be perfectly honest, in certain light, and depending on what she was wearing, Sinead’s hair did pick up a reddish glint. In any case, it was lovely hair, sometimes held back with a ribbon or tied in a ponytail. That was my favorite, because it showed off her sweet face from more angles.

Okay, I’ll admit it, I was well and truly whipped. Why else would I have endured shaving off my Arctic beard with a straight razor, a steel relic from another century? Victor kept his gray beard trimmed short with a comb and scissors no matter where he was, down in Argentina, above the Arctic Circle, or here in Ireland. At his age, he had no expectation of finding female companionship, or for that matter, of impressing anyone at all with his appearance.

He looked at me very sternly. “Dan Kilmer, you are completely out of your mind. As we both know perfectly well.”

“Victor, if I bring Sinead on board, then I’m going to show her the Caribbean. That’s just how it is.” No matter what was happening in the rest of the world, winter in the Caribbean was a paradise for visiting sailors, just as it had been ever since Columbus had first set eyes on it. Five centuries later, some of the islands still had their economic and political acts together, providing a safe venue for commerce. Voyagers who could pay their way in hard coin, or who were bringing a desirable cargo to sell, were always welcome to drop anchor—and I was willing to test Victor’s patience by spending the winter season in the eastern Caribbean with Sinead.

It was my schooner, after all, and he was not the most agreeable company to begin with. We were never equal partners. I was the sole owner and master of Rebel Yell. He was the German-trained doctor who lived on my boat, a man who read dull, often indecipherable books, blurted callous remarks to strangers, and occasionally stitched me up when my hide required patching.

He folded his hands and looked at me coldly. “When we sell the rest of the diesel, then we will divide the profits?”

His blunt question did not surprise me. For the past few years we’d operated on a 25 percent basis, with one share of our income for Hung, one share for Victor, one share for the captain, and one share for the boat. You could say that meant two shares for me, but if you knew how much my old steel sailboat demanded for her upkeep, you would understand that I was being very generous in offering each member of my permanent crew a one-quarter share in our mutual endeavors. Our provisioning costs came out of the boat’s share. Hung was given the required coinage, and he gimped ashore anyplace we dropped anchor to explore the local markets and bring back what he could find for Rebel’s galley.

Our formal divisions of the loot did not come at regular intervals, because our profitable endeavors were infrequent and unpredictable. Victor also had sporadic income from his services as a physician. Neither of us had any off-boat investments or foreign bank accounts. The global economic crash had wiped out all of that years before.

“Victor, do you want a fresh accounting right now? Here? Or can it wait until we’re back on board?”

He leaned back in his chair and folded his arms across his chest. “Just so you know: when we reach Argentina, I think I will be leaving the boat.”

So that was it. I’d sensed some irritation at my intention to bring a new girlfriend along for an ocean voyage, but this was the first time in at least a year that I’d heard him mention jumping ship. “Do you mean you’re just going walkabout for a while, or are you planning to leave for good?”

“At this point, I’m not sure. How long would we spend in the Caribbean?”

“At least through January.” Doctor Victor Aleman was always prickly, and the prospect of the skipper bringing a new female on board had made him more so. But Sinead Devlin was certifiably gorgeous, and she’d already left her scent in my cabin. And I wanted more of it—a lot more of it—but not in cold, rainy Ireland, with the northern winter fast coming on. Island-hopping around the Caribbean with Sinead could be a life-changing experience for both of us. She could even be The One. In that case, maybe it would be good-bye to cranky old Doctor Aleman, and hello to sweet young Miss Devlin. I would just have to be more careful to avoid being shot, stabbed, or run over without a resident sawbones on board to put me back together.

After a minute of studying the dark ceiling beams of the pub he replied, “Yes, of course, the northern winter is a good time to be in the Caribbean. Martinique and Guadeloupe would be very nice to visit again, as would Saint Maarten and the other Dutch islands. Excellent bookstores. And we might see some yachts we know.”

Right on all counts. Unspoken between us was the fact that a fresh cut of the cards was offered to a sailor in every new port of call. Hundreds of voyaging yachts would be cruising around the Caribbean over the winter, with some of them bound for every point of the compass between Canada and Cape Horn. The services of a European-trained orthopedic surgeon were always in demand, even a moody son of a bitch like Victor. He could do his doctoring from boat to boat in the major anchorages without ever putting a foot ashore or having to deal with local officials or bureaucrats. And then he would meet well-connected people and hear about interesting employment situations. If he found a better position, it wouldn’t take him an hour to pack his seabags, and even less time to say good-bye.

For that matter, if things didn’t work out between Sinead and me, once we were in the Caribbean she might wind up aboard another yacht sailing back across the Atlantic to Ireland, or to anywhere else. Even Hung might eventually decide that he’d had enough of life afloat. Anybody who tossed their bags aboard my schooner was a volunteer, free to go at the time and port of their choosing.

Nobody was a prisoner aboard Rebel Yell except the captain. Without my care, she would rust away and sink, but I would never let that happen, not while I drew breath as a free man. Rebel was more than just my mobile home; she was the one place on the planet where my footsteps landed on my own sovereign territory. Sixty feet on deck and eighteen feet wide across the beam, she constituted my movable micro-state: Dan Kilmer Land. I repaid Rebel’s faithful service to my needs with my own fierce loyalty to hers.

****

I tried to understand Victor’s urge to leave the boat to revisit the land of his birth. The bastard son of a Nazi had no living family who would accept him as their kin, so family reunions were out of the question. Any remotely possible inheritance had been wiped out during the worldwide economic crash. All the wealth he possessed was on my boat, either hidden among his possessions or awaiting a new division of the profits from our last salvage expedition; the reality was that Hung and I were the only family Victor had.

When he returned to Buenos Aires, he would look for a few old friends. Place una ramita de flores on his murdered wife’s grave. Visit former schools and neighborhoods, the haunts remembered from his youth and early adulthood. Maybe he would return to my boat, maybe he wouldn’t. For all I knew, he might fall in love with a rich widow or be kidnapped by gangsters, the way his wife had been. Or he might join another medical do-gooder group, to suffer harder penance than could be found aboard an old schooner.

It didn’t matter. If he decided to go, he would go. He was pushing sixty; maybe he felt that he had little time left to reconnect with his origins and find some cosmic meaning to his life. Perhaps declining health and vigor or the fear of creeping dementia lying ahead were giving him a new sense of urgency. For whatever reason, his walks up into the Irish hills were getting longer and longer. Something was eating him, but his private thoughts and inner motivations were always an enigma to me.

After the Caribbean, Rebel Yell would spend a few months knocking around the boatyards of the River Plate for a much-needed refit. According to rumors being cast across the radio waves, the yards in Uruguay were still functioning. But if Victor didn’t return to Rebel after going walkabout, I would move on without him. I wasn’t getting any younger, either. Unless I found the right woman, eventually I would be sailing solo again when the septuagenarian Hung jumped ship, fell overboard, or simply failed to wake up one morning.

Reconnecting with old friends and family was a frequent thought in the mind of a rootless vagabond sailor. Going home could be painful, though. What if nobody was still around who even faintly remembered your past life there? In that case, your entire existence upon the planet Earth held no more lasting meaning than a random pebble tossed into a pond: the few ripples were soon gone, leaving no mark. In a zero-sum world, your life might as well not have been lived.

So maybe there was more driving me to invite Sinead Devlin aboard than just her pretty face and soft curves. I wasn’t even forty, just a decade older than her. She was still in her fertile years, and I had time to make a family, time that had already run out for Victor. Still in her twenties, Sinead would also be acutely aware of her ticking biological clock. Judging by her behavior in my private cabin over the past week, her alarms were all clanging away. We’d been careful, so unplanned offspring were not yet a part of the equation. Thus far.

****

The prior months spent in the Arctic in the company of two older men had left me with an abundance of desire for youthful feminine charms. I was lucky in my choice of Irish smuggling ports, meeting Sinead Devlin on my second night in Crowhaven. Never married, no kids. Riding out the hard times with her family, like everybody else. She was not put off by my old Marine Corps souvenir, the scar that ran from under my right eye toward my ear. I had been attempting to reel her in for two weeks, and she had stayed overnight on Rebel Yell for the past two nights. If things worked out, there was a good chance that Sinead would be on my schooner when we left Ireland bound for the tropics.

That morning, I had brought Sinead back to shore in my old Avon RIB, the rigid-hulled inflatable boat that was Rebel’s dinghy. Pleasant and relaxed during breakfast aboard my schooner, she seemed to stiffen and withdraw as we approached the quay. We tied the dinghy to the floating small-boat dock beneath the stone wall and climbed the angled bridge onto solid ground. She went ahead of me up the narrow ramp, giving me a welcome opportunity to admire her curves from behind and below.

At nine in the morning there was nobody in sight on the small landing. But after spending a night of unbridled passion in my cabin, Sinead now seemed mindful of showing any slight public display of affection. I settled for a quick hug and a brief kiss before she pulled away and unlocked her bicycle, which she’d left chained to a section of iron fence. It was hard to understand Sinead’s sudden shyness after her unrestrained behavior in the privacy of my cabin. I guessed that this was an Irish Catholic cultural affliction, and I hoped to cure her of it in the warm and sunny Caribbean.

If I’d had a car, I would have given her a lift home, but I didn’t, so I couldn’t. It would take hard physical effort to peddle steeply uphill to her home in the village of Golleen, but returning to sea-level Crowhaven would be an easier decision for her. She would be able to fly downhill, coasting most of the way straight back into my arms. “See you again tonight?” I asked her.

“You might see me, you might not. I have to look after my sister and my mum.” She pulled the chain from the fence and dropped it into the basket in front of her handlebars, along with her small overnight bag.

I reached for her shoulder, turning her to face me. “Sinead, are you going to come sailing with me or not? Last night—”

“Last night I was out of me head!” Strands of auburn hair spilled across her cheek as she tilted her head and gave me an exasperated look. “Oh, Danny, you know I’d love ta go off sailin’ with ya on your lovely boat, you know I surely would. If all I had ta do was pack my bags, they’d already be packed. Don’t you know that by now?”

“What about tonight, then?”

“Oh, you know I’d love to, but I have obligations. Real obligations. I’m not free as a bird to fly away. My life is ever so much more complicated than yours.”

“Sinead, I want you come with me. Maybe just for a year, and then I’d bring you straight back here to your family. But maybe for forever.”

“And I want to go, don’t you understand that? But it’s not that simple!” She shook her head and pulled away, both hands firmly set on her handlebars, looking up the road. The sea-breeze chill had left her cheeks rosy.

“Okay, I understand.” So, was this the kiss-off? Her last good-bye? I hoped that I was misreading the moment, but I couldn’t push the issue without sounding desperate. “Hey, well, listen—if you hear anything new about buyers, you can reach me at the pub. We still have thirty drums.”

“Aye, and I told you there’s a fella nosin’ about. But nothing specific, you understand. You’ll be the first to know if I hear anything.” A quick peck on my cheek and she mounted her bicycle, gave me a final smile, turned, and pedaled away.

Some people might observe my lifestyle, tally my few and brief semi-meaningful relationships, and assume that I was a confirmed bachelor by choice. But the truth was very different. I’d been trying to find the right woman for years. The problem was finding someone who could live aboard my old steel schooner for longer than just a voyage or a season before jumping ship for drier and steadier pastures. After a decade afloat I was still looking for that one special lady who would surrender her home, her family, and her friends for the watery seafaring life. A woman who would not try to drag me ashore to live out my days imprisoned between white picket fences and square walls on the unmoving land.

My novels are available on Amazon in print, Audible and Kindle formats. Here’s the link to my Amazon author page.

Or, you can get them straight from me, and I’ll sign them. The old PO box works, great, today it surprised me with an original Red Cliffs painting, but PayPal is faster, at this link.

Very nice! Always great to get unique goodies out of left field.

On another subject, you really should get away from Paypal; they are distinctly unAmerican. (I haven't used them for 20+ yrs!) Try one of these or do a search of your own:

https://paralleleconomies.com/5-patriotic-payment-alternatives-for-ecommerce/

Anyways, I'm going back thru your stuff and am almost done with "Reconquista." I think I started buying your books when you appeared on Mike VDBs site, or definitely at Pete's place, WRSA.

Damn, now I'm feeling old! Take care, man!

Excellent. Your analysis of current events is a national treasure.